Behind the Chute

Documenting “firsts” can be difficult, specifically when it comes to racing innovations. Today’s common and mandatory use of parachutes to slow a 325 mph fuel car has fuzzy roots. It is generally agreed that the first chutes were used in NHRA around 1959. They soon became mandatory for cars that could run 150 mph.

Mike Dunn, former Team Mopar® Top Fuel driver and current president of IHRA, has had first-hand experience in chute-stopping power, since he grew up at the track from infancy with his father, Big Jim Dunn.

So, who was the first to use a parachute to stop a drag car? “My guess would be it was someone like Art Arfons,” says Dunn. “He used to run a front-motored dragster with an Allison airplane motor in it before he went to jet dragsters. He’s the kind of guy I think would try using parachutes back then.

“My dad’s first altered car in about ’62-’63 used the old military-style chute. Those chutes hit hard. I remember it had rubber bands in it when they packed it. That car ran 9.40s at about 150, which was fast in those days. It won a lot of races.”

Dunn took on the job of re-packing parachutes at the track when he was 14 years old.

“Back then, chutes were important because, in some cases, short shutdown areas, but mostly because the brakes were not nearly as good as they are today,” Dunn says.

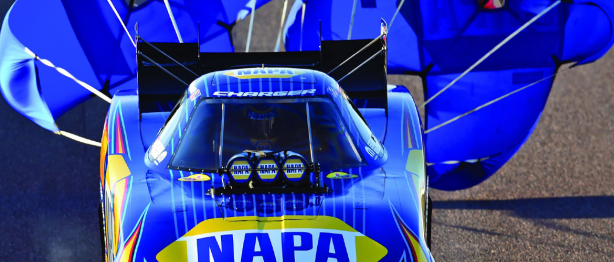

Today’s specifically designed drag racing chutes differ greatly from the old military design. “The big difference with today’s chute design is they don’t hit so hard,” he explained. “In Top Fuel, negative g-force can be minus 6 Gs when you pull the chutes. Joe Amato once detached his retina from the chutes hitting so hard.”

The Deployment Line

“There’s a couple of ways to do it,” Dunn says. “My dad taught me to drive into the chute, where you actually pull the chute while you’re at wide open throttle. You try to time it where that chute would hit right where you lift (off the throttle).”

There’s good reason for good timing. A car travelling 300-320 mph will travel over 300 feet before that chute actually hits. “I would pull the chute about 100-150 ft. before the finish line, at about the first mph light,” says Dunn. “Drive it just past the finish line, step off the throttle, grab the brake in case the chute didn’t open; then, when I felt the chute open, I would let off the brake and coast through it.”

Things Change

“When I first drove in match races, I’d get to halftrack and put my hand on the chute lever,” Dunn explained. “If I made it to the finish line, I’d pull the chutes or, if it blew up, you’d pull it because you wanted that initial impact of the chute to scrub off a ton of speed before the chutes got burned off. A lot of times, they got burned off. That would save your ass.”

Fond memories of parachutes seem to provide great fodder for racers.

“Back in ’97 or ’98, I think it was the Mopar Top Fuel car in Topeka, I was in the semifinals against Kenny Bernstein in a really close race,” Dunn said. “I drove into it and pulled the chutes like always, and the car blew the rear tire out right in the lights. It destroyed the back half of the car, but it never crossed the center line because two things happened: one, the chutes came out, and two, I was lucky it didn’t take out the wing.”

Parachute technology does not have to make great leaps and bounds forward anymore. The last 50 years of common use, design and testing have produced chutes that deploy softer, stop quicker and are more dependable than they have ever been before.

0 Comments