Plymouth’s Back With a Velocity Stack

Standing by a milling machine since the age of seven, it’s not surprising if you eventually carve your own intake manifolds out of rectangular aluminum blocks. A series of well-considered decisions, a commendable dose of humility, and Anders Hammarbäck from Karlskoga now owns one of Sweden’s most stunning Road Runners.

“I remember it like yesterday,” says Andreas Jansson from the Swedish town of Karlskoga. “He contacted me for the first time in June 2017 and sent me a photo shortly after. I nearly fell off my chair.”

The picture depicted a 1969 Plymouth Road Runner with a row of pipes sticking up through the hood. The number of muscle cars in Sweden with trumpet stacks and Weber setups under the hood could probably be counted on two hands – especially within the Chrysler group.

Hammarbäck himself says, “Had it not been for Andreas, the Road Runner would still be a well-kept secret outside Karlskoga’s city limits.” A thankful nod to Andreas seems more than appropriate.

So here we are, a few years later. The car has been photographed, and Hammarbäck speaks about it over an occasionally crackling phone line.

“Well, it wasn’t a Road Runner that initially caught my eye,” Hammarbäck says. “I was looking at Challengers and ’Cudas. Then this one popped up on a big national car market online. I acted fast and drove down to Skärblacka outside Swedish town Norrköping.”

What he found was a car in very good condition – unlike the rust buckets he had looked at previously. Given that Hammarbäck had already interrogated not just the current owner but also the previous one, Leif Tynell from Vellinge, Skåne, he knew quite a lot about the car.

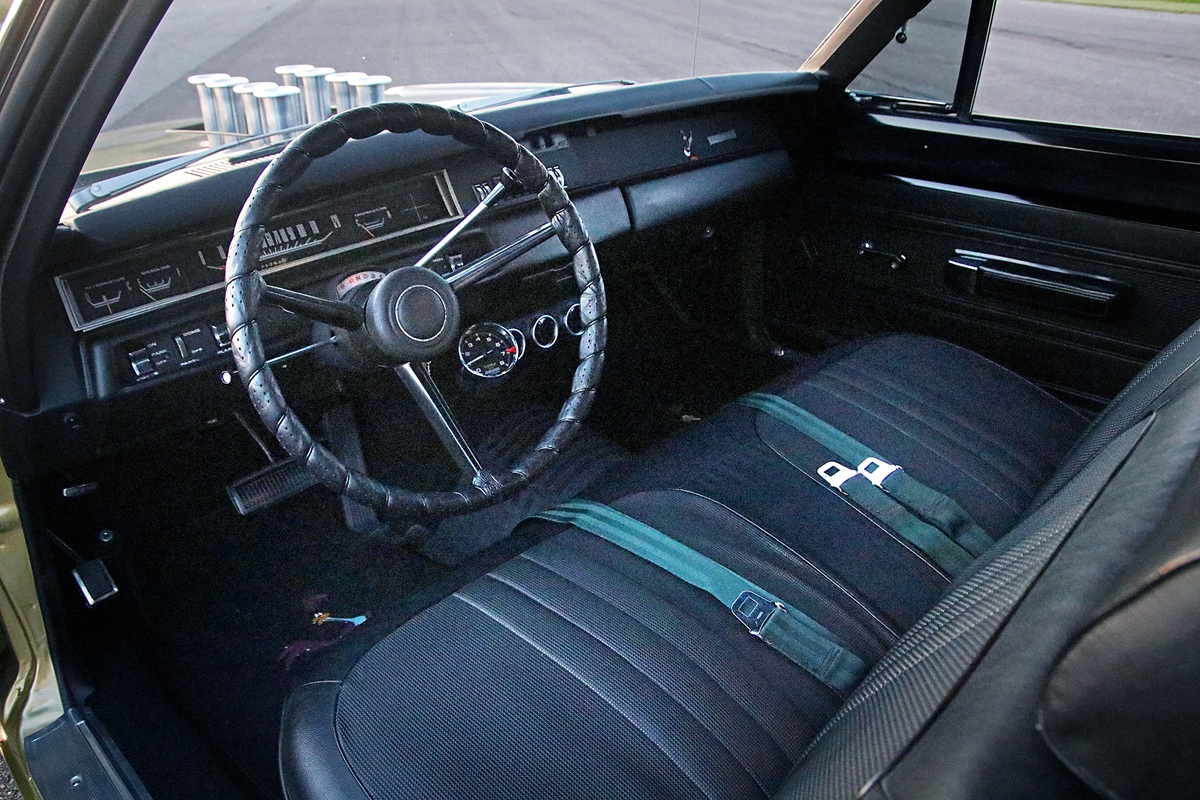

“Yes, I probably knew more than Kjell Larsson in Skärblacka. For instance, that Tynell had reupholstered the interior and that his neighbor had repainted it in some Peugeot color. But I didn’t mention that. What Tynell had told me, however, was that the body was in exceptionally good, almost untouched condition. Only a small area near the lower edge of the rear window, the size of a fifty cent coin, had been repaired

for rust.”

Eight years ago, Hammarbäck became the proud owner of a Plymouth – a relatively satisfied one at that. He is the third Swedish owner since the car arrived to Sweden in 2008 from Longwood, Florida.

Before we dive into the most obvious feature of this Road Runner – the V8 – I can’t help but ask Hammarbäck what he’s done with the car overall.

“Not much, but there’s always something that breaks. It’s American, and it’s old. So the odds are stacked against it,” Hammarbäck says with a big smile.

During the first few years of Hammarbäck’ ownership, most of the work revolved around fixing broken components. Then the itch started – while the car had been restored to its original state, Hammarbäck decided it was time to inject some fun. This meant getting rid of steel wheels, hub caps and skinny tires. Orange-painted valve covers and a stock V8 just weren’t enough.

“I’d worked with Webers before, albeit on Volvos. So I wasn’t entirely unfamiliar with these carburetors,” Hammarbäck explains.

And so, Webers it was – or rather, Fajs, Chinese replicas of Weber carburetors, which Hammarbäck managed to acquire for a fraction of the cost of genuine Webers.

“If you buy a new Weber 48 in Sweden, it’ll set you back around 600 dollar per carburetor. I got these for 140 dollar each,” Hammarbäck says.

Four carburetors for less than the cost of one Weber – quite a steal. Hammarbäck, who bought them on a whim, was especially pleased to find they looked good quality-wise. All he needed to do was carefully go through each one to ensure they were in perfect working order.

Before installing the carburetors – or anything else for that matter – the 383 engine had to be dismantled. It had started misfiring and running poorly.

“It turned out the camshaft was worn down. One of the lifters had a hole in the bottom. In one cylinder, the valves barely opened,” Hammarbäck explains.

Time to invest in a new camshaft – a roller cam, to be precise, which costs a bit more but is generally more reliable than a standard camshaft.

“I went with a COMP Cams Thumpr cam. It has a wonderfully lumpy idle. Interestingly, this camshaft is designed for a single large carburetor and a traditional plenum intake manifold – not four carburetors with eight individual intake runners. But it worked out fine… up to about 6,000 RPM.”

Beyond that, the back pulses shot straight up into the carburetors, as there was no “pressure equalization” in a non-existent plenum chamber.

“The windshield got completely soaked with fuel. But the V8 ran flawlessly at low and mid-range RPMs. It had incredible torque.”

To address this issue, Hammarbäck swapped out the camshaft again, this time for a roller cam from Howards, chosen with great care.

“This camshaft is a bit milder – a good mid-range cam. A tip for setups like mine with individual runners is to choose a camshaft with a wider lobe separation angle,” Hammarbäck says.

The result: significantly less fuel on the windshield. Though, at full throttle, the V8 still snorts impressively, with tiny fuel sprays escaping the stacks – a sight that only adds to the car’s charm.

Originally, the 383 had stock iron heads, which were replaced with aluminum heads from 440 Source.

“These aluminum heads are supposed to deliver 500 horsepower, but after I ported them, they looked ready to produce double that. They had several flaws, like sharp edges in the ports that created turbulence. How to port heads? The channels need to be equal in volume, which you can test with

liquid. As for valve lapping, you’ll probably get 100 different answers if you ask 100 people…”

Hammarbäck adds that while one valve face angle ensures a good seal, the others shape the airflow around the valve. However, you don’t need too many angles unless you’re building a pure race engine.

Many shy away from tuning four carburetors. Not Hammarbäck. He calmly notes it’s like tuning two Webers on a Volvo B20 engine – just double the number and take twice as long. Once tuned, they stay that way.

The throttle linkage also posed no challenge.

“I built my own solution, with a throttle roller in the middle. It works very well. I even connected the transmission to it; the throttle controls the oil pump. At full throttle, the transmission shifts fully. There are many solutions you can choose from. Ford owners often run their throttle cables from the side, but I opted for a setup running along the engine,” Hammarbäck says.

What about EFI and other modern innovations?

“EFI is good; I can’t deny that. But if you want EFI, why not just buy a new car instead? Go back to the golden days of Ferrari, Lamborghini and Alfa Romeo – they all used Webers or Dell’Ortos. A well-tuned carburetor mixes fuel as well as electronic injection.”

Hammarbäck acknowledges that carburetors don’t account for altitude, temperature or humidity, but these factors only become critical in serious racing.

Before concluding the conversation, I ask Hammarbäck about one of the coolest features of his Road Runner: the entirely custom-made intake manifolds – a necessity when dealing with Mopar® vehicles. The available options are limited.

“I started with an engine without an intake. Using an empty beer can and a tape measure, I began roughing out the height and geometry. Then I designed it in CAD. The runners transition from round to rectangular. Usually, you’d use a five-axis milling machine for this, but we only have a three-axis machine.

So, I had to make five different fixtures to complete the milling process.”

How long did it take? After a pause, Hammarbäck admits, “It was a while ago. My kids, now seven and eleven, were much younger then. When my wife and the kids went to bed at 10 p.m., I’d head to the workshop. I’d work until one or two in the morning, then get up at five. You can’t keep that pace for too many nights in a row. I had to plan carefully.”

The strategy worked. Today, Hammarbäck owns one of Sweden’s most stunning Road Runners – a testament to ingenuity, persistence and passion.

0 Comments