“It should look like a 1968 Dodge Dart HEMI®. An LO23. At least 700 horsepower, and a four-speed manual transmission.” That was Caj “Cajan” Carlsson’s vision about seven years ago, when he set out to build what might be Sweden’s most badass Dart. Now the car is finished – at least as finished as a car can ever be.

“Forty were made with manual transmissions. Another 40 with automatics. So, 80 in total. Mine is a clone of how they looked back then,” Carlsson says.

Yes, an LO23 clone – a tribute to a car Dodge built specifically for the dragstrip. Sold without any warranty whatsoever. Getting your hands on one of the 80 originals – any that still exist after being raced hard nearly 50 years ago – is almost impossible. And expensive. Think drag racing on the dark side of

the moon.

So, he built his own LO23. Not cheap either, but easier. It turned out fairly close to the original, with equally unique parts – like the transmission in Carlsson’s Dart.

“It’s an A833. 18 splines. A Super Stock transmission for an A-body. A so-called HEMI gearbox. Built by Passon Performance with Red Stripe gears. The cover is aluminum, and the casting number indicates the case is from 1968. I’m the only one in Sweden with this kind of transmission – and probably the only one in Europe.”

He adds that these Super Stock gearboxes came with two gear sets: one for racing, one more street-friendly. The racing gears are what’s known as Red Stripe.

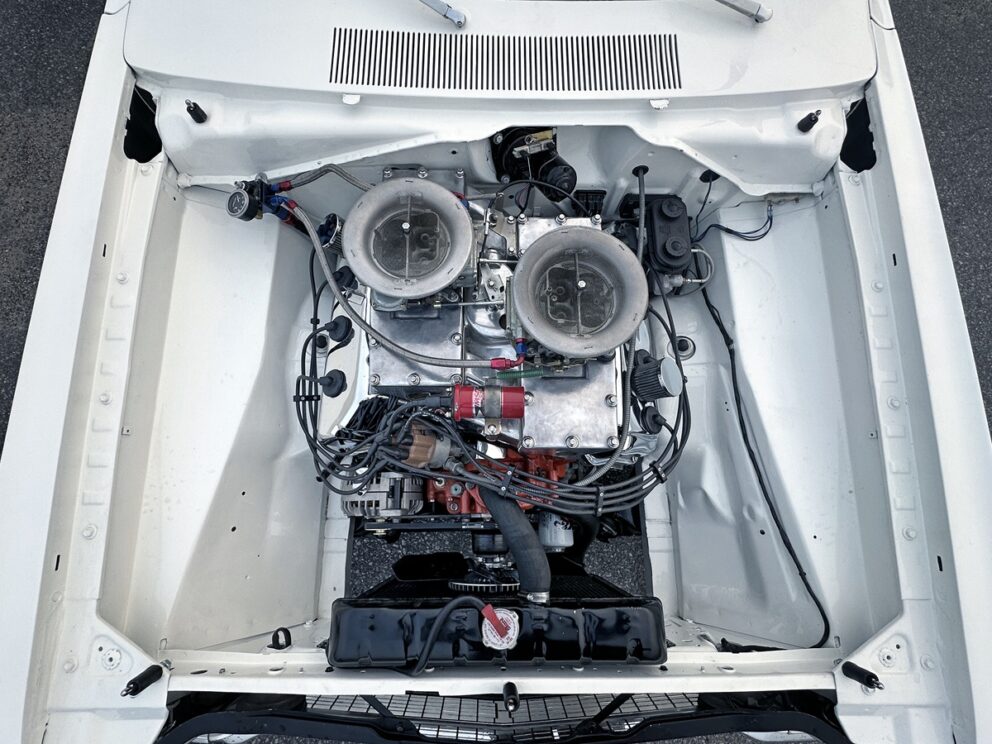

And the engine – the HEMI? Well, the L023 V8s had slightly higher compression ratios than stock HEMI engines. They had a different camshaft and the distinctive cross-ram intake with dual carburetors. It’s believed that dealers even tweaked them further for extra performance. The LO23s were making over 600 real horsepower, according to many credible sources. Carlsson’s? A bit more – he doesn’t specify. His HEMI engine has been stroked to more cubic inches than the original 426.

“I bought the engine in parts from the U.S. and assembled it myself. Ed Victroy in the U.S. ported and flow-tested the heads, which are Stage V units. They’re fitted with Stage V stainless rockers. I’d guess those heads would run about $12,000 here in Sweden.”

It’s top-tier stuff, like the rest of the V8 build. The block is from Mopar® Performance, cast sometime in the 1980s. The forged steel crank – a stroker from Callies – brings the HEMI engine to 472 cubic inches and makes it eager to rev. The rods are Mahle H-beams. The JE pistons are custom-made, deliver a compression ratio of 10.75:1 – pretty street-friendly. Crower made the camshaft, a solid roller.

“How often do I need to adjust the valves? Not very. I usually say that if you’re adjusting often, you’ve done something wrong. But sure, if you’re running Chevy V8s, you’ve got Chevy rocker geometry. So yeah, you’re wrenching. A lot…”, Carlsson laughs.

He adds that he’s confident the tuning work done in the U.S. is solid – because he went through every part and measured everything before and during the engine assembly. Everything matched spec.

The cross-ram intake? Also from Mopar Performance. Slightly better than stock. The Super Stock carbs are Holleys, each rated at 780 cfm. One right-hand, one left-hand – built specifically for the cross-ram layout.

And the oil pan? A specialty piece from Charlie’s. A bit unique. The oil pump, made by Keith Black, isn’t mounted inside the pan but externally. The pickup, a swivel type, sits inside the pan. External oil lines route up to the pump.

So yeah, you could run this Dodge on a road course without starving the engine of oil?

“Or drive on the rear wheels. Ha ha! It actually had wheelie bars when I bought it, but I cut them off.”

Before we finish talking about the engine and drivetrain, Carlsson shares more details. He’s running a Hayes steel flywheel and a dual-disc clutch from McLeod, rated for 1,000 horsepower. It’s a mechanical clutch, not hydraulic. That’s a plus, Carlsson says, because it’s easier to fine-tune and offers better pedal feel.

The three-inch driveshaft sends the power to – yes, you guessed it – a Dana 60 rear axle. Thirty-five spline axles hold up well, and the gear ratio is 4.11:1.

One thing Carlsson’s Dart shares with the original LO23 is the rear brakes: 11-inch drums. That was the setup in 1968. But the front brakes? Not so much.

“They’re Wilwood discs, 11 inches, with four-piston calipers. The car stops instantly when you press the brake pedal. Yeah, the brakes are solid.”

Keep in mind: there’s no brake booster in Carlsson’s LO23 clone. No power steering either. The engine bay is clean and minimalist – nothing in the way when it’s time to wrench.

How close is Carlsson’s build to an original LO23? Well, the front brakes are a deviation. But that’s somewhat compensated by the velocity stacks – including steel carb filters.

“These are original parts. I bought them unused, in the original box. These Super Stock stacks were used in 1964, 1965 and 1968 with the HEMI. But sure, I don’t have the A100 seats. That’s where I stray from the LO23. I’ve got back problems. So, the build isn’t nerdy down to the last detail. I’ve built the car exactly how I want it,” Carlsson says.

The Dodge A100 seats were used in racecars from the mid-1960s because they were the smallest and lightest in the Mopar lineup. That’s it. But for a bad back, they offer zero comfort.

A fun detail – nerdy, if you will – is the Dart’s rear wheel arches. The classically hacked-up openings to accommodate big, grippy tires. Here, the stories diverge. Some say Dodge barely cared how they were cut. Others, like Carlsson, claim there were fairly precise measurements.

“The wheel wells were already cut in the U.S. before the car arrived here in 2006. Comparing mine to an original LO23 shows a lot of similarities. I can’t find the exact dimensions right now, but I’ve got them written down somewhere. It’s about the radius, the distance from the door to where the arch starts, and the distance from the rear of the arch to the body line before the bumper.”

According to the Dart’s VIN, it began life as a GTS model with a 383 cui V8 and a four-speed manual. Carlsson says roughly 900 units were built with that engine/transmission combo – a small fraction of the over 182,000 total cars produced.

Rewind about seven years to when Carlsson bought the Dart. It all started with a deep craving to own a 1968 HEMI Dart, LO23 or not. But after trips to the U.S. and inspecting several candidates, Carlsson ran into multiple issues.

“I looked at a few red ones, but the prices were around $125,000. Then I found examples with billet wheels and digital dashboards. That ruins the car, if you ask me. So, I decided to build my own 1968 HEMI Dart instead.”

Carlsson started by hunting for a Dana 60 rear end. Eventually, he found one mounted to a car in the small Swedish town of Tierp. He asked for photos and made a discovery.

“It looked like it was installed on a Dart. So I asked the seller – and sure enough, it was a 1968 Dart. Structurally sound, despite some dents in the rear body panels from all the stress of countless dragstrip runs.”

Carlsson went for it. Axle and body in one shot – for a decent price. A flying start.

Then the real work began. The rear axle was mounted with coilovers and ladder bars, which were replaced by Super Stock leaf springs from Mancini Racing. Plastic windows were swapped for real glass. With a stripped cabin – save for a roll cage – it was time to chase down a dashboard, steering column, door internals. Carlsson bought an OEM fuel tank and installed it. Then a brand-new wiring harness and new chrome. New carpet, new headliner. The list was long, the evenings longer. The hacked-up wheel wells and front subframe also needed fixing.

The hood with the HEMI scoop? Fiberglass – not original, but it’s been with the build for a while.

“You’d think it would be easy to find a clean front subframe, but it’s tough to find one that’s not bent or butchered. How long did it take to build the car? Seven years. But it always ended up last on the priority list because I was drag racing a front-engine dragster. That took all my time.”

And the paint? A white base – RAL 9010 – with a clear coat on top. A tip from the internationally known artist and car painter Ray Hill.

During the photo shoot, Carlsson casually mentions that he rarely outsources anything on his builds. With this Dodge, he only farmed out the valve seat cutting and crankshaft balancing. The reason? Why pay someone to do it if you end up redoing it anyway?

“I even milled the main caps for my 392 HEMI that I run in my front-engine dragster. They were the only parts that held when I blew that engine a while back…”

Besides the 392, Carlsson has owned a few Mopar vehicles – mainly Plymouth Road Runners. And then there’s the story of his very first car.

“Yeah, the first car I bought after getting my driver license in 1981 was a 1971 Dodge Challenger with a 340 cui V8. White with a black interior. Loaded with options like a rear-window defroster button on the dash and a Slapstick shifter. I paid $3,300, and when I sold it in 1987, it had done 83,000 kilometers.”

But that wasn’t the last time Carlsson saw that Challenger. Recently, 37 years later, he visited Mel’s Garage, a well-known Swedish dealer of classic American cars.

“I recognized the Dodge immediately – even though it’s black now and has a 440 under the hood. With a hefty price tag around $71,000. I didn’t even need to check the license plate.”

Why? Simple. Back in the ’80s, the power steering locked up on Carlsson, and he drove into a rack of oil cans at a BP gas station. The left front fender and outer headlight bezel took a hit. Carlsson did his best to straighten it out, but the bezel was never quite the same. And despite the car now being beautifully

restored, that bezel has never been fixed.

“That must be the only thing that hasn’t been replaced on the car over the years. Kinda odd. They even asked if I wanted to buy it back – but the price didn’t quite align with my wallet. But… I still have the original 340 engine in my garage at home…”

0 Comments