Turbine Technology

— Was considered to be a contender as the engine of the future

— Vibration-free turbine engine could run on peanut oil, diesel, kerosene, gasoline and other combustibles

— Made an appearance in a 1964 movie which helped generate publicity

The Chrysler Corporation was involved in and pioneered the development of gas turbine engines for passenger car use since World War II. A gas turbine engine is basically a small-scale jet engine, simply stated, how it works is that incoming air is compressed and then heated (by the burning fuel ignited by a single spark plug) inside the huge combustion chamber. Those extremely hot gases expand, spinning exhaust-side internal turbine wheels which in turn drive the wheels of the vehicle.

George J. Huebner, a Chrysler employee that started with the company in 1931, was the main guy, the brains, the motivation behind the project, an extroverted engineer with big dreams. He headed up the Chrysler Turbine team and was assisted by fellow engineers Bud Mann and Sam B. Williams. Turbines as used in jet aircraft were run mostly at wide-open throttle, and cars were run normally at half-throttle or less.

The 1950s saw the dawn of the new “Jet Age” and the public clamored for things that were futuristic, and a jet-powered car certainly fit the bill. This new powerplant was all about less moving parts, and because of its design, it has continuous gas flow and no reciprocating motion. Early on one of the main challenges was when the driver mashed down on the accelerator pedal, there was considerable “lag” before it would hit full-rate output. And this acceleration lag was very noticeable (seven seconds).

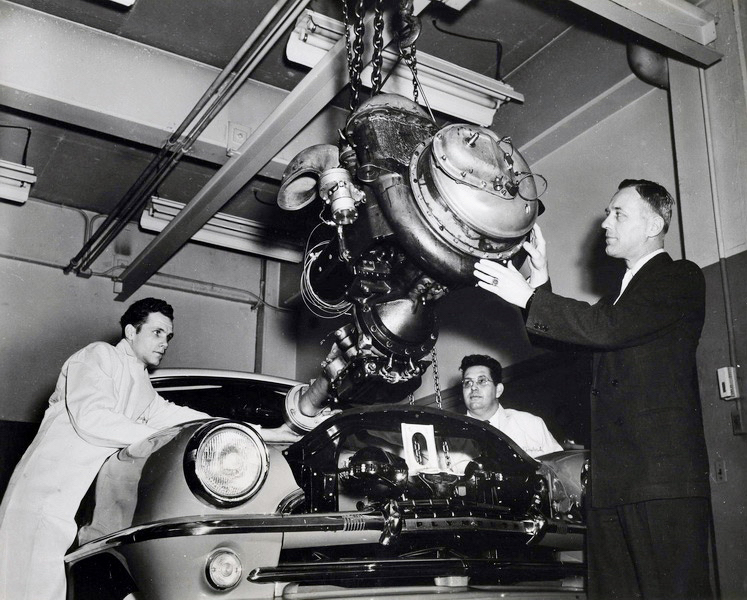

Dr. Huebner and crew shown here with the CR1 turbine with transmission attached, being installed into the 1954 Plymouth Belvedere which became known as the GT-1001. It generated 100 horsepower to the output shaft, which was said to be equal to a conventional 160 horsepower engine at that time period.

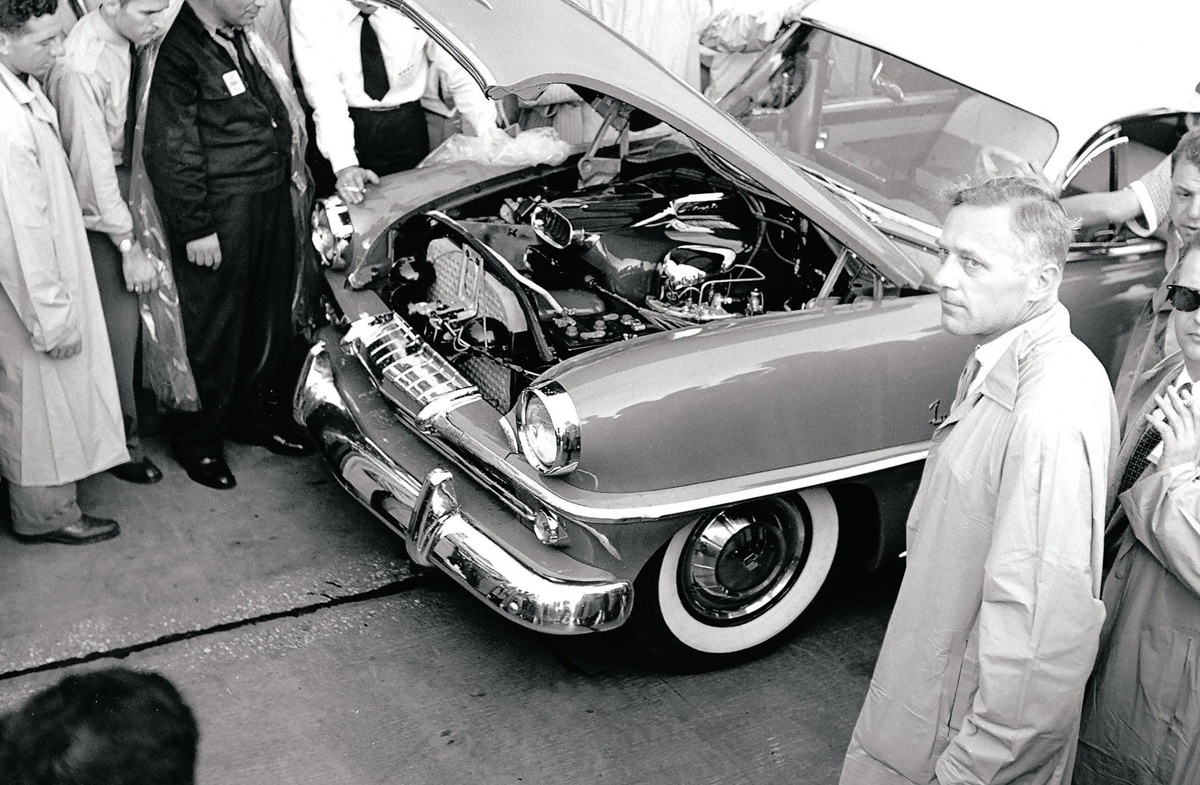

Everywhere the Turbine Plymouth went there were crowds around it! Except for the tail pipe that looked different, the outside of the Belvedere body didn’t look any different from a normal car. When the engine was heard and when the hood was open, then it was a huge attention grabber.

EARLY MEDIA

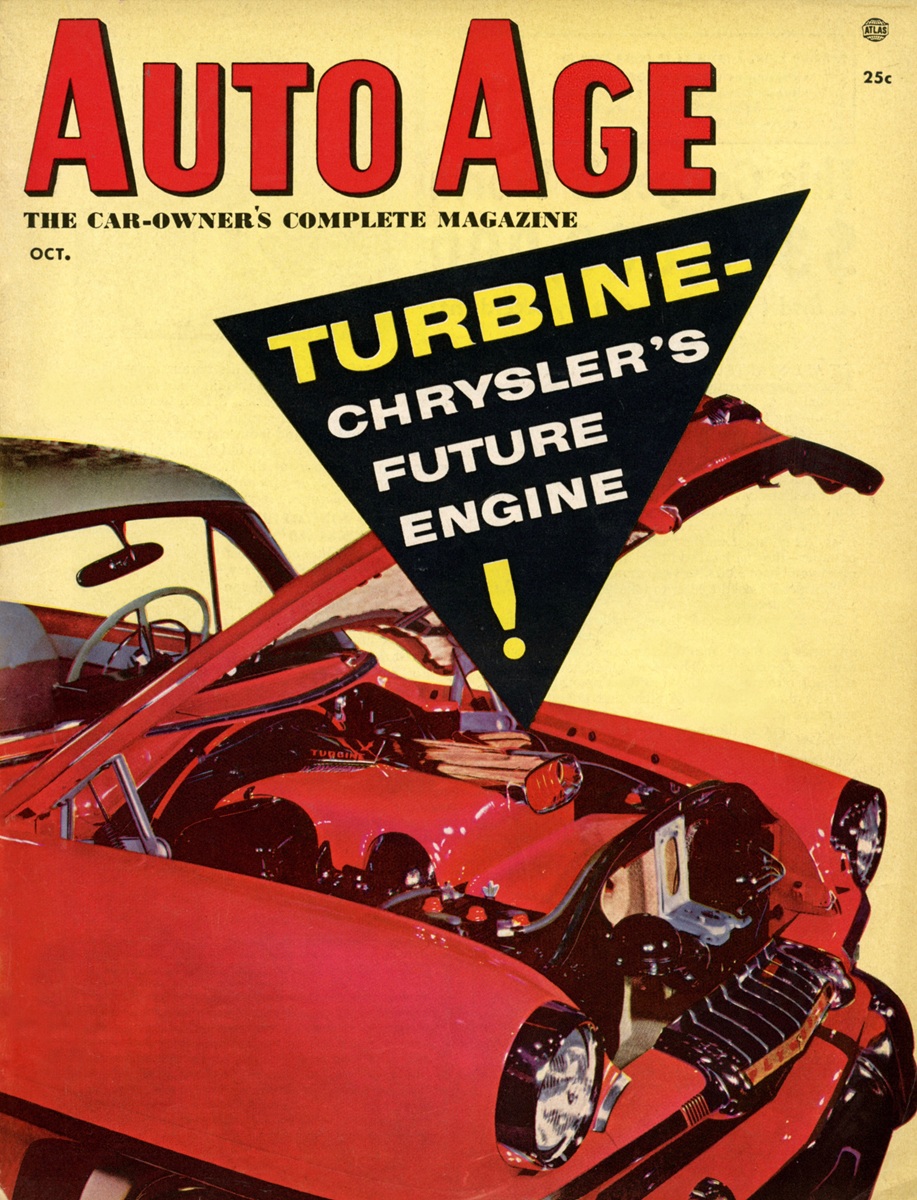

Gracing the cover of the October 1954 issue of Auto Age Magazine, the 1954 Plymouth Turbine car was featured and the article was penned by Chrysler engineer George Huebner. He listed three requirement the Chrysler turbine project had to meet, at that time: 1) its fuel economy equals that of present-day piston engines of similar power output; 2) its exhaust is cooler than that discharged by today’s conventionally powered cars while 3) its test performance is far beyond that of piston engines of comparable power.

New for all 1955 Chrysler cars was the “Forward Look” body styling, and beyond that, this particular ad specifically for the 1955 gas turbine-equipped car (with special center-mounted large exhaust outlet) was one of the early advertisements for the turbine program.

This car, a 1956 Plymouth Belvedere, was driven cross-country (from New York to LA) averaging around 13.5 miles per gallon, and was driven no faster than 45 miles per hour. Gasoline was cheap and it was clear that even though the turbine could run on a variety of combustible liquids (peanut oil included) the logical fuel was either diesel or gasoline, and it was “unleaded” gasoline that was required. One point that was made and it did have some veracity to it. “Even in its present, infant stage of development,” said George Huebner, who was behind the wheel on that 3,000-mile trip, “the gas turbine’s performance rivals that of piston engines which have had a design history of more than 100 years.”

SCI-FI ON WHEELS

What could be more alluring than traveling down the expressway in this futuristic turbine-powered machine? This 1961 “Turboflite” was designed by Virgil Exner to entice the automotive-buying public all about the (possible) upcoming turbine technology. The firm Ghia in Turin, Italy, was responsible for the body and it measured some 218-inches in length thanks to that narrow, pointed front end. The bizarre opening roof design and open front fenders surely made a lot of observers scratch their heads. For night-time driving, there were two headlights that dropped down (landing gear style) in front of the front tires. Luckily, none of the styling cues of this car were transferred to any production cars for the automaker. (The rear wing was actually hooked up to the braking system, and pivoted to aid in slowing down the car at high speeds. A deceleration air flap for assist in safe stopping.) It was a show pony only, this car never drove and was only pushed in and out of exhibit halls for displays.

1962: DODGE AND PLYMOUTH

This is the turbine that was fitted in the 1962 Dodge and Plymouth cars and each individual generation was a work in progress for the engineers, they were always after decreasing throttle lag, increasing mileage and later into the program, trying to control NOx emissions.

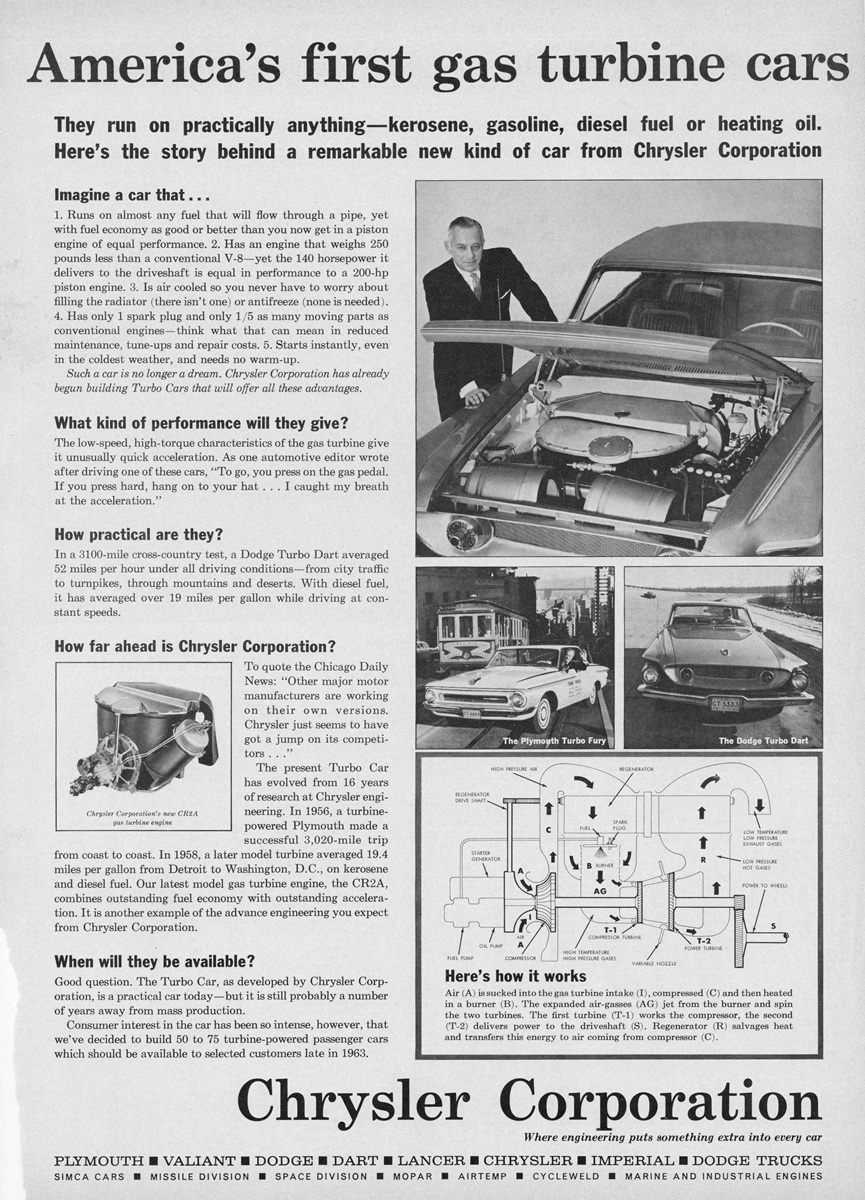

There were national advertisements on the cars, such as the 1962 versions that had seen improvements in fuel mileage and drivability. One has to wonder what real effect, if any, all of the promotional work done on the various turbine cars did in terms of sales increases on the available productions cars. No turbines were sold to the public at any time and the advertising was always careful not to claim that Chrysler Corporation had any concrete plans for turbine-powered vehicles.

The 1962 Turbine cars (Dodge Dart and Plymouth Fury) had customized grilles, which unlike the production cars, didn’t cool the engine but allowed for air entrance for the intake of air for the turbine itself. These two cars were called “Turbo-Dart” and “Turbo-Fury” which related to the term “Turbo-Jet” that was used in aircraft applications for turbines and not for being equipped with a turbocharger.

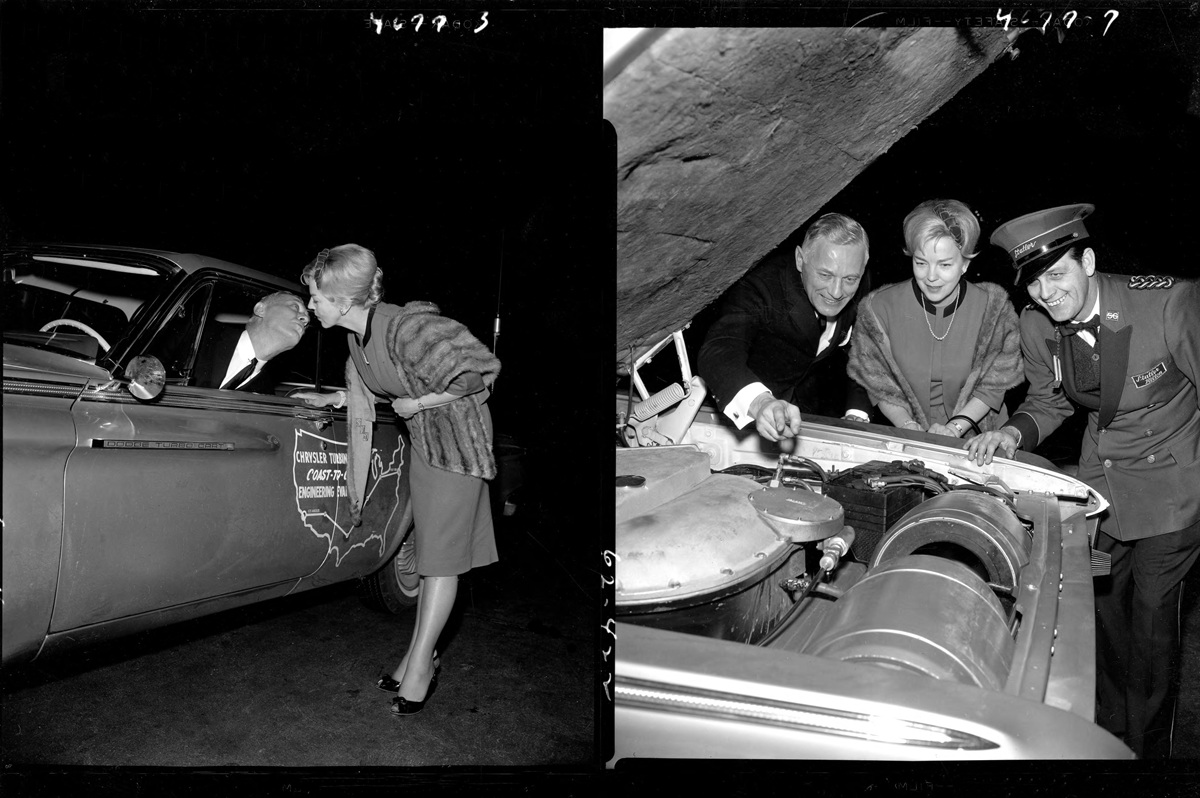

ON THE ROAD

One thing about engineer George Huebner, he wasn’t shy about publicity! Here he is in New Your City saying goodbye to his wife Trudy prior to driving the Turbo-Dart cross-country to Los Angeles…and when he arrived he spent several hours with local press showing them the details of the car. A marketing man all the way besides his engineering and development savvy.

LIGHTER THAT PISTON V8

No radiator required on the turbine! This demonstration shows that the 450-pound turbine engine was lighter than a commonly-used Mopar® V8 engine at the time, shown here the 318-cid “Poly” engine.

1963: CHRYSLER TURBINE CAR

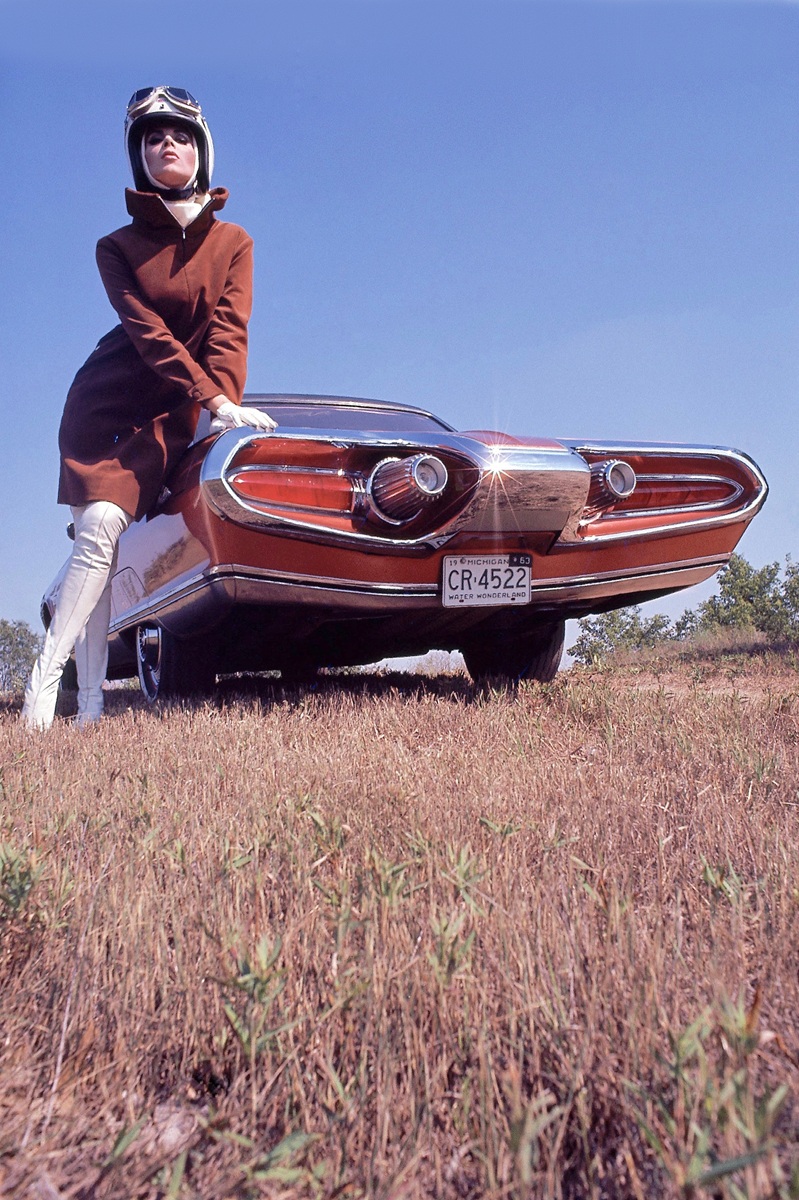

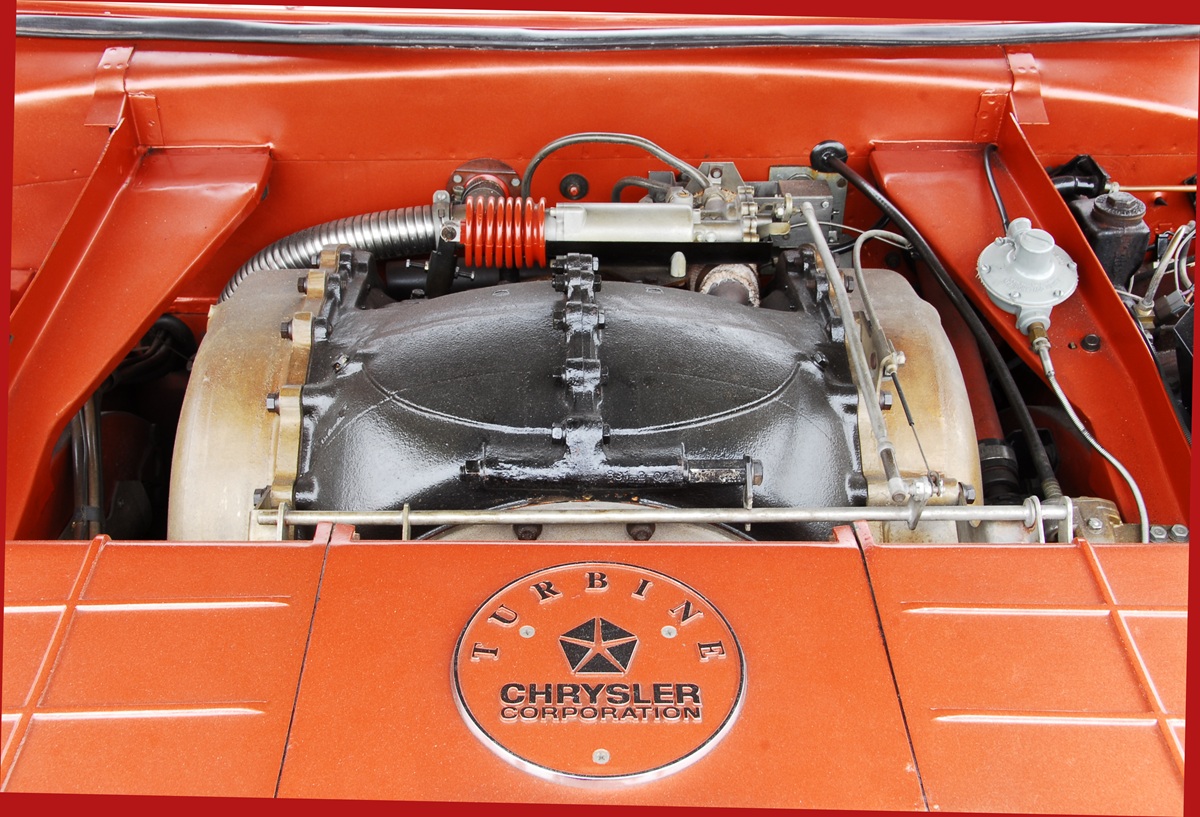

The story of the fleet of 1963 Chrysler Turbines has been told numerous times and to cover all the specifics of those cars, it would take a whole other article of this length or longer on these futuristic experimental vehicles! The reason that Chrysler built the cars (55 in all) was to get them out to the public so to get accurate feedback on what the people thought of them, with honest answers and with real-live day-to-day driving experiences. One of the big deals when you got past the wild looks of the body lines done up in Fire Frost Copper paint was fuel mileage figures. While the testers knew the cars would run on diesel, unleaded gasoline or heating oil, almost any type of combustible liquid, they found that the fuel mileage was comparable to typical internal-combustion engined cars of the era, however while idling the turbine engine went through a lot of fuel, as the engine spun at between 18,000 and 22,000 rpm just idling!

Some of the well-known facts about these cars: many felt they had unimpressive performance, there were over 30,000 people that signed up for the 203 spots to get the cars loaded to them (for a three-month time period), over 50-percent of the people that drove them said that they would consider buying a Chrysler turbine-powered car in the future (depending on price), the cars were heavily styled after the Ford LaGalaxie show car from 1958, coil spring front suspension was used rather than the normal torsion bars for Chrysler production cars, and when one of the cars toured Mexico, the president of Mexico thought it was a fantastic automobile and personally drove it, and at that time it was fuel by tequila!

“Ecology” became an important part of the automotive world and the industrial world in the middle 1960s and smog in major cities (Los Angeles in particular) was so bad that kids were not allowed to go to school on the bad smog days. Emission controls were major concerns for Detroit auto makers as government standards had come into the picture and in a big way. California had come up with special standards required for car manufacturers in order for them to be sold in the state. The Chrysler turbine engine wasn’t clean enough to be considered a viable source of power for any production car use and all the attention to clean up tail pipe emissions was shifted over to the line of cars that had the conventional powerplants, which was ALL of them.

“It quickly became apparent that we were up against a situation that would require everything we could throw at it:’ Huebner said at the time. “That was the problem of oxides of nitrogen (NOx), a major component of Los Angeles smog. It was a case of all hands to the pump to check NOx emissions on the conventional piston engine. Experts in this area were hard to come by and our most able engineers were in the turbine project. They moved over and explored catalysts and exhaust manifold reactor systems to reduce chemical emissions on our internal combustion engines. meanwhile, turbine work stopped except for some experiments with its combustion and metallurgy”.

Be it the uniquely-style interior appointments or the heavily styled front and rear treatments, complete with rotary blade themes, this 1963 Mopar automobile was an attention grabber even without knowing what was under its hood!

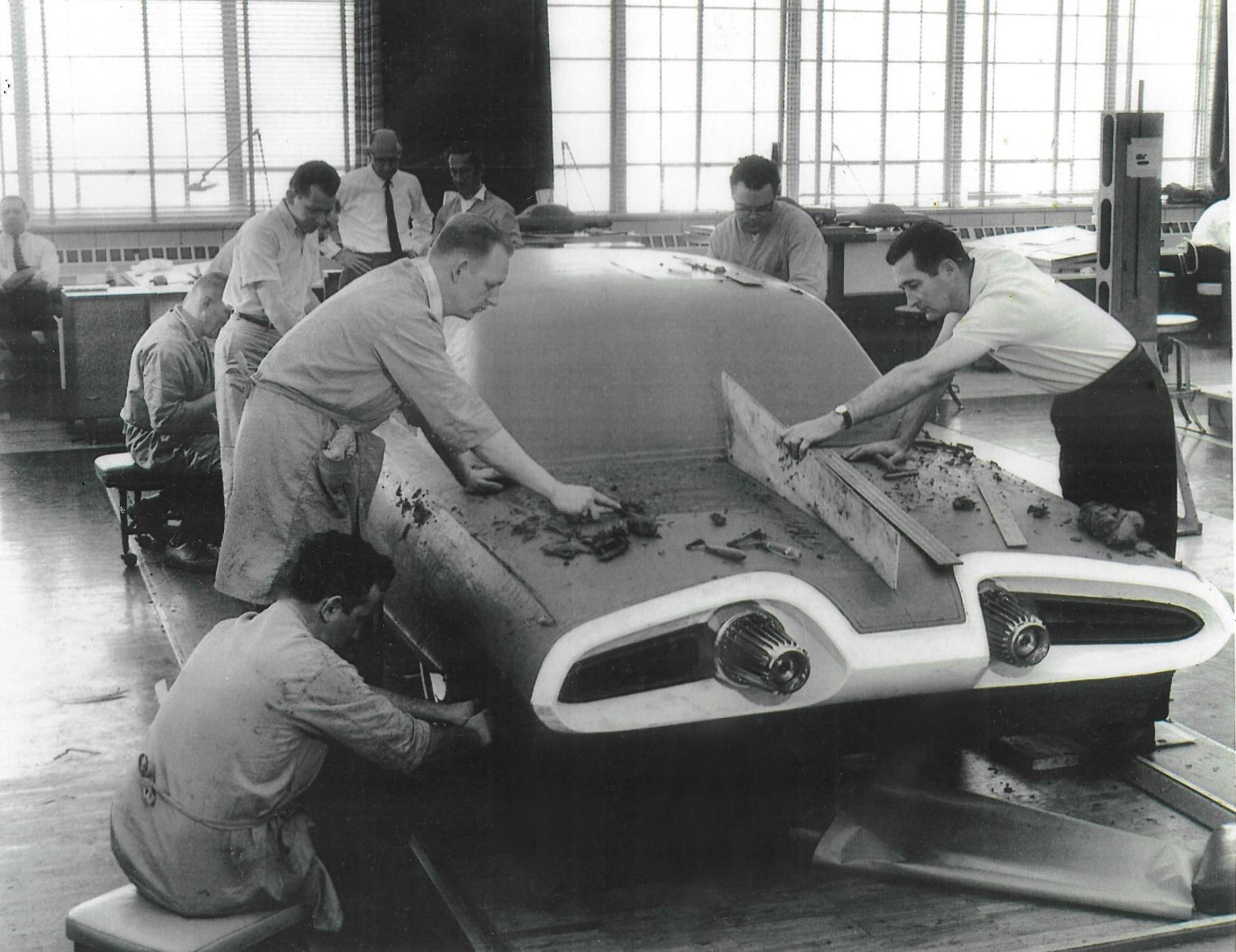

From the initial clay mockup to the final assembly line, these turbine cars were very special and gave the general public a glimpse of just how involved the Chrysler Corporation engineers were always thinking and coming up with ideas!

After the program of the fleet of 1963 Turbine cars had come to an end, it was determined that the big part of what killed the whole deal was the upcoming smog concerns that were very real for the American automobile industry. Sadly, at the end of the program, all but nine of the car were destroyed, as the reasons listed by the company was 1) the exorbitant import tariffs that it would have cost to keep them all in the USA (or the expense to return them to county of origin, Italy. 2) the company didn’t want to see the cars sitting on used car lots and/or have the engines replaced with regular piston engines. Destroying concept cars was nothing new for Detroit automakers, however, in this case, because so many were destroyed in was almost considered a crime against humanity. Thank goodness Jay Leno has one!

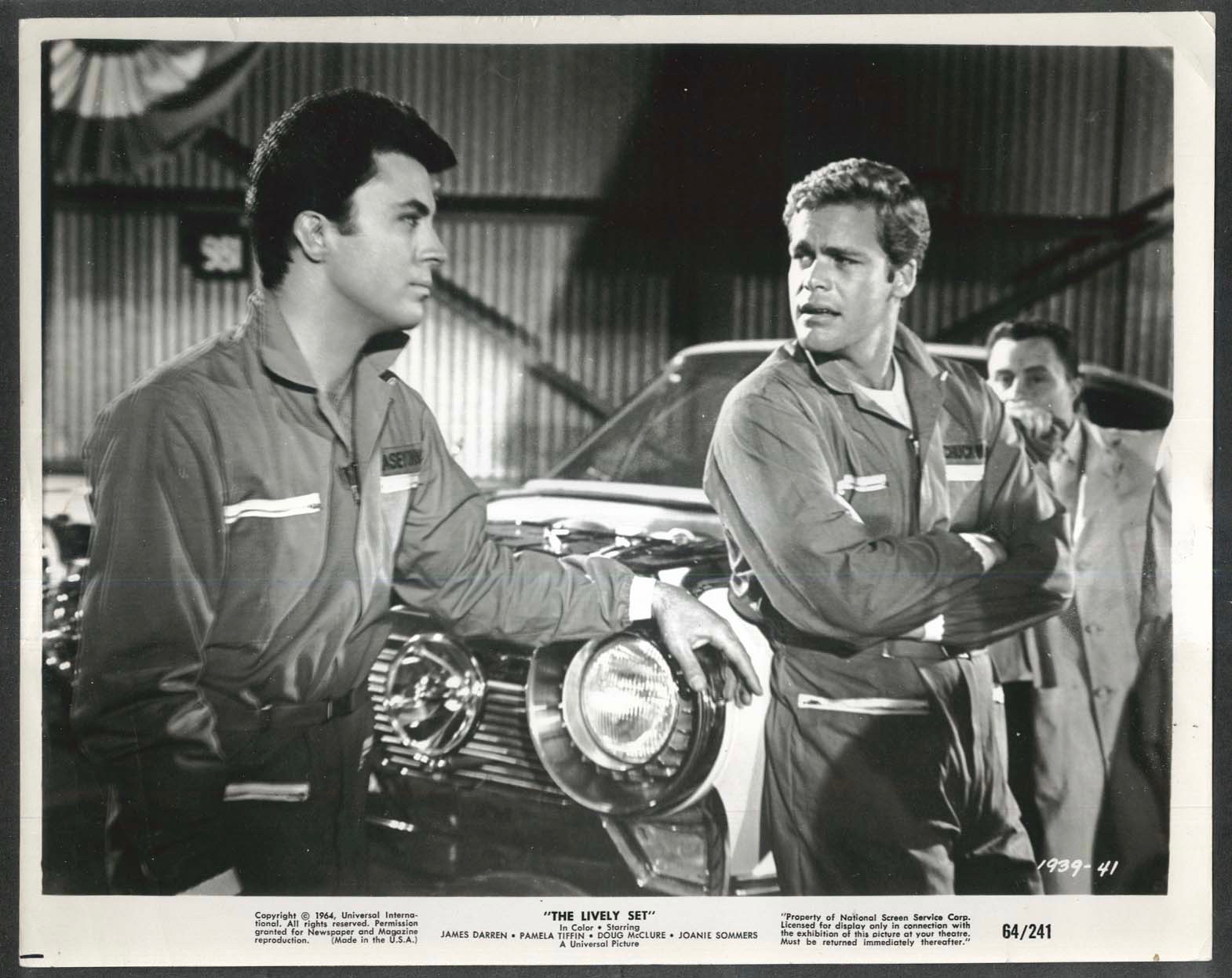

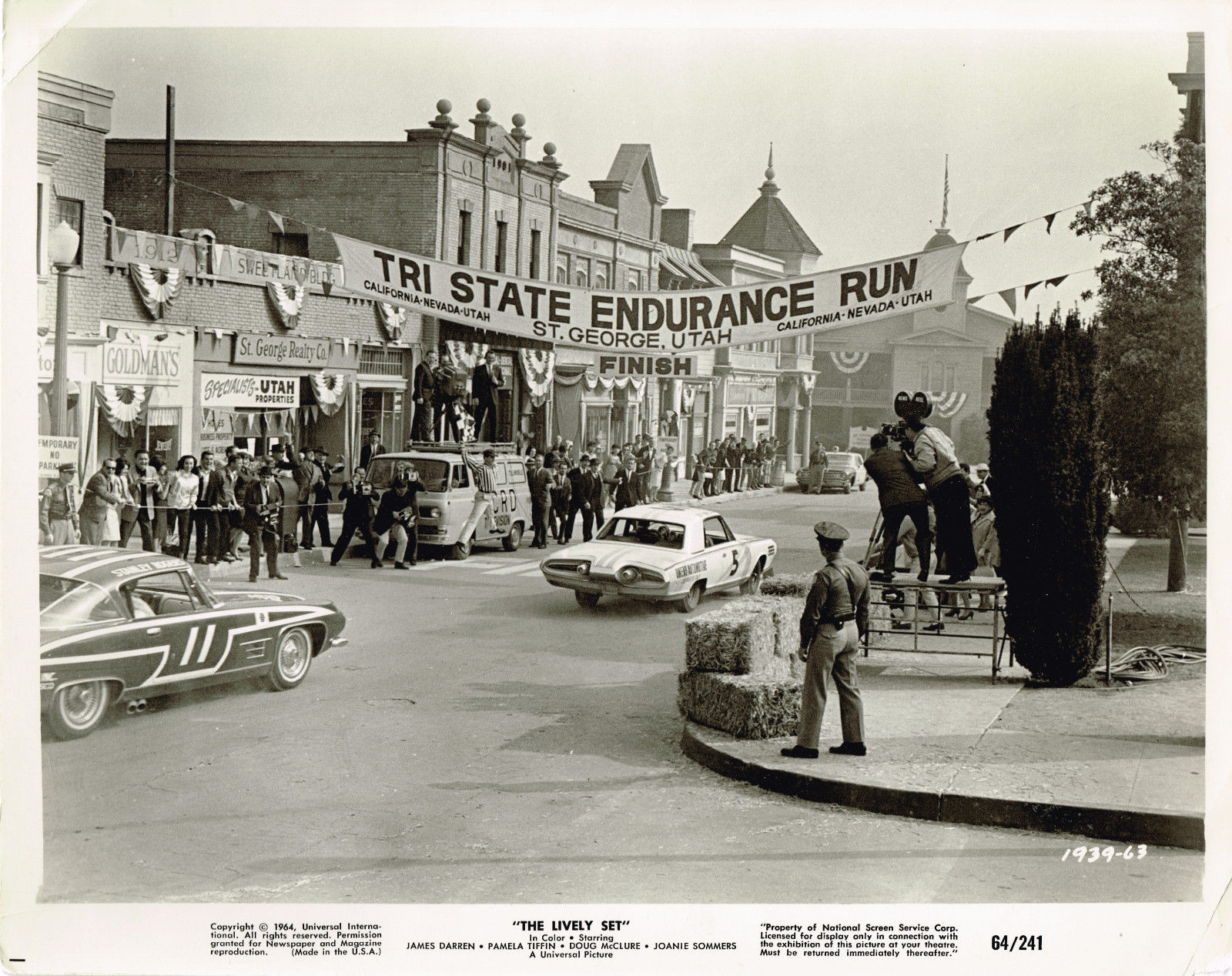

THE LIVELY SET MOVIE

Chrysler supplied one of the cars (which was painted white) to the producers of the 1964 movie “The Lively Set” (James Darren, Pamela Tiffin, Doug McClure), painted white with blue stripes and prominently featured. The story line was about a young man building a revolutionary turbine engine, highlighting its innovative technology all the while playing it up as the “engine of the future.” Mickey Thompson was included in some of the racing action scenes.

In 1970 George Huebner did an analysis of alternate power sources for the United States Department of Transportation, which included stream, electric and the Chrysler turbine engine, for long-range prospects. In his study he found, and no nobody’s surprise (after all he was a lover of the turbine engine all the way!) that he concluded that the best of the three to move forward with was with turbine power.

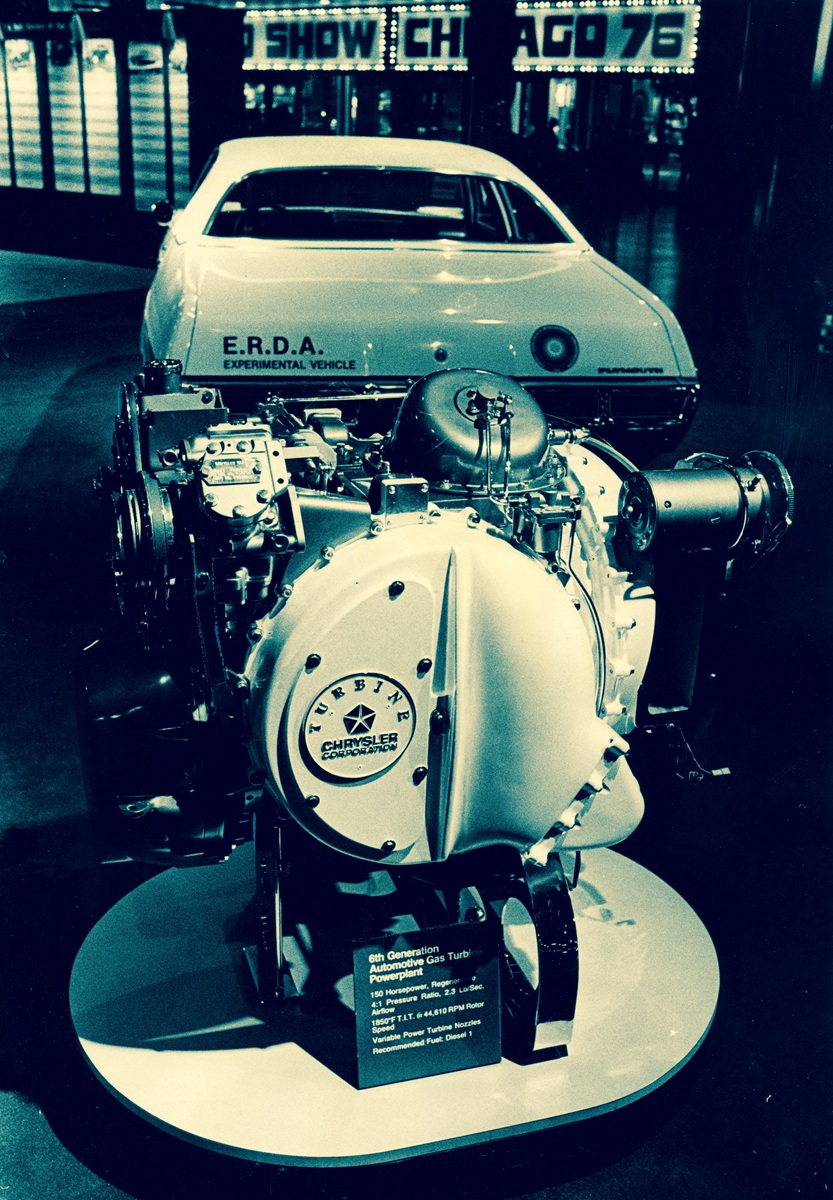

It was then in its sixth-generation, and the Chrysler turbine engine had made big improvements with reduced throttle lag and also had shown decreases in fuel consumption. It had also been discovered that the Chrysler Turbine had developed better compression braking qualities. While there were still issues regarding high manufacturing costs and that there were problems to get the turbines to reduce their NOx emissions to acceptable levels. What was needed was an influx of money for continued research and development.

It took a few years, but soon there was some forward movement on the Chrysler turbine program, and it came from the U.S. Government. 1972 saw the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and that new government agency awarded Chrysler Corporation with a contract worth $6.4 million to do further development on the viability of the use of turbine engines for automotive use. But things were changing swiftly at Chrysler at this time. The whole thing came to a screeching halt when Lee Iacocca had to ask the U.S. Government for a 1.5-billion dollar load to keep the company afloat. The government eventually said yes, however one of the many conditions was to axe the gas turbine development efforts, as it was clearly not a mandatory expense for the company.

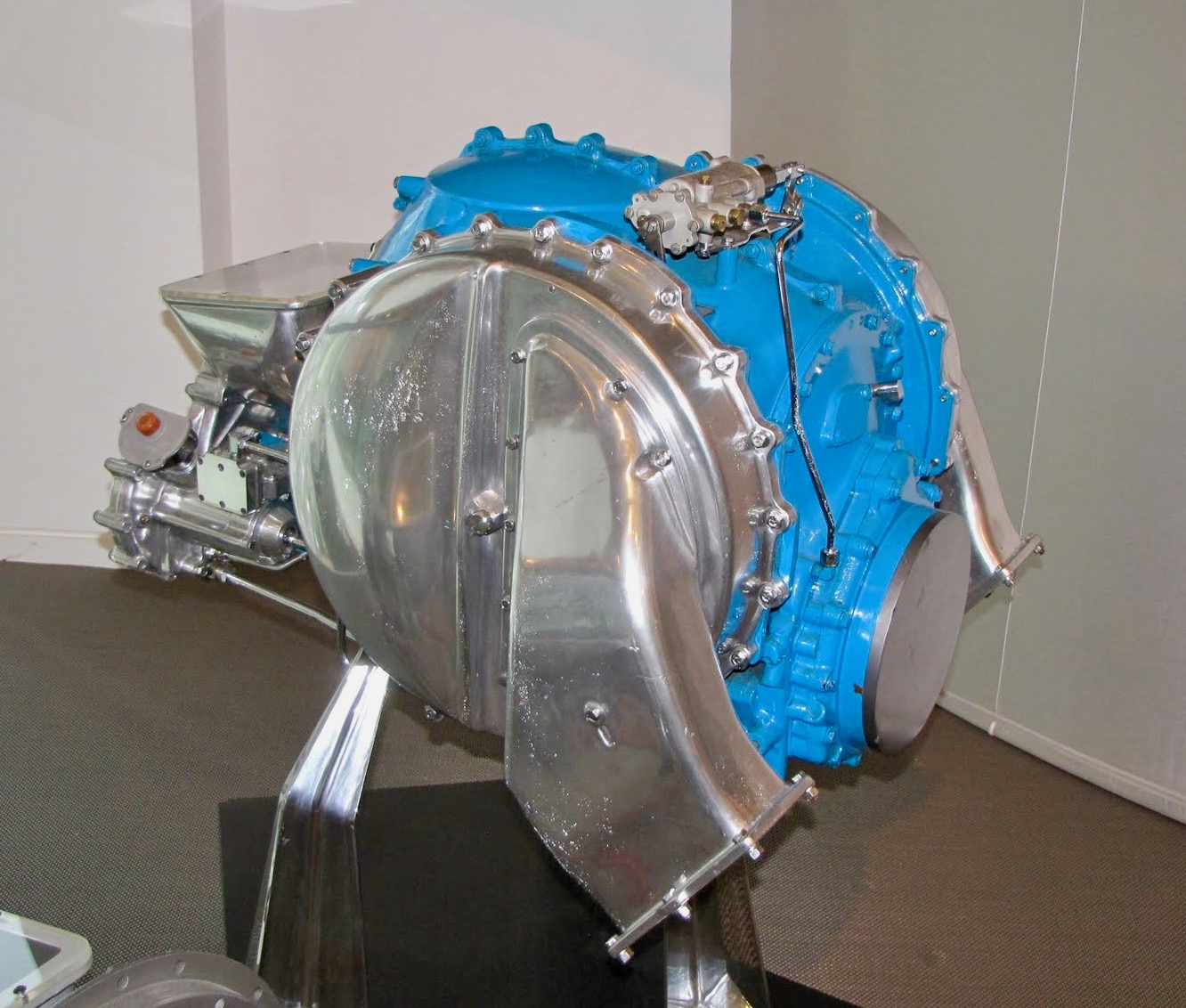

This 1976 image shows the Chrysler turbine display at the Chicago Auto Show, behind the white cover is a regenerator, or heat exchanger, and there’s one on each side of the (Generation Sixth) engine, which developed a peak power outage of 150 horsepower). The only reason Chrysler was doing any development work on the turbine engines was because they had been awarded a government contract (the company was at the time in financial dire straights, and dreaming up a new powerplant was not anywhere near the top of their priorities to survive).

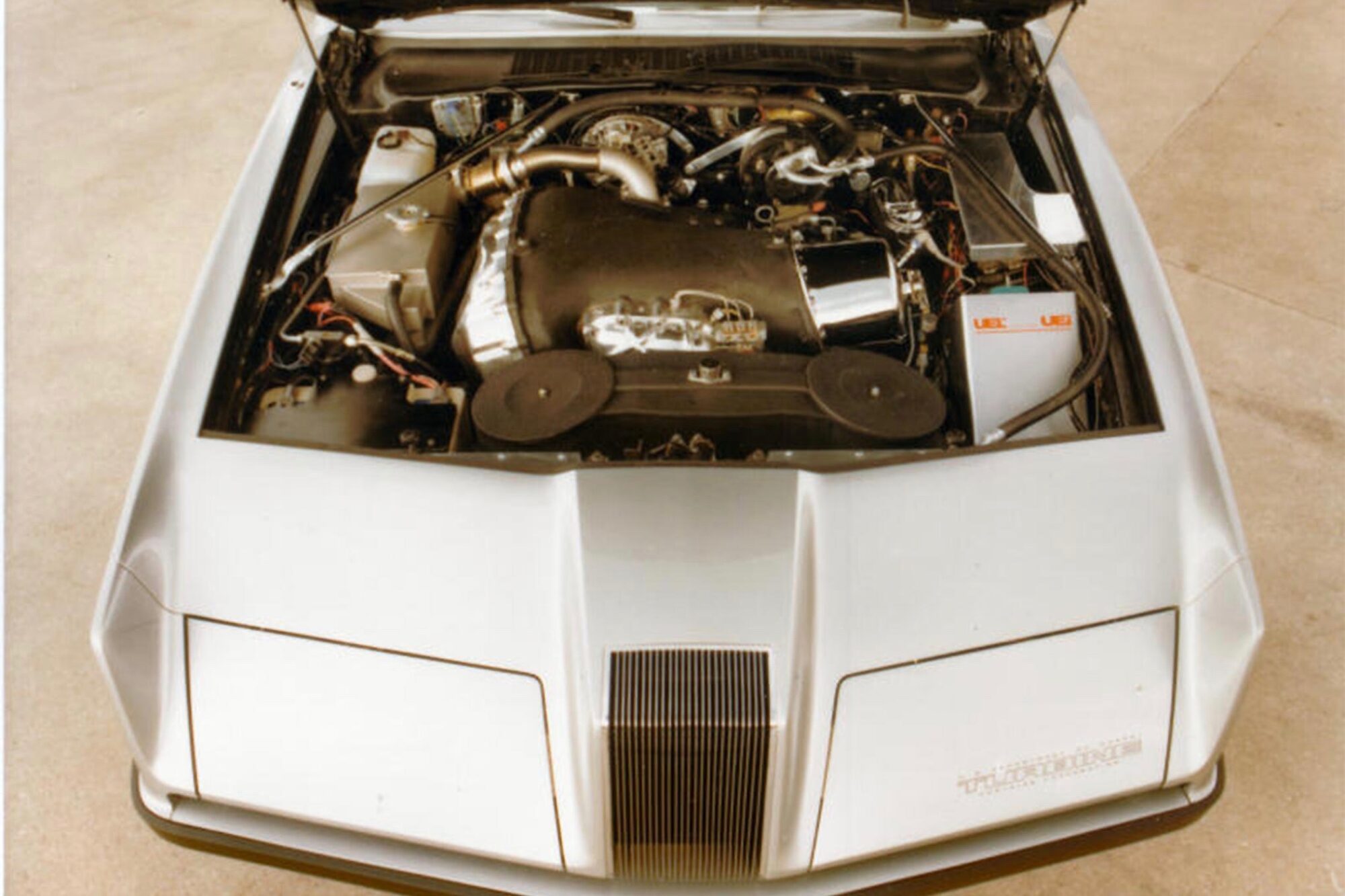

LEBARON CONCEPT

Built for the U.S. Department of Energy, this Turbine Concept featured a distinctive aerodynamic front end treatment and the body design (based on the 1977 Chrysler LeBaron) was carried out by Bob Marcks. The group was determined to build a truly viable gas turbine for production use, the Chrysler engineers had faith at the time it would actually happen!

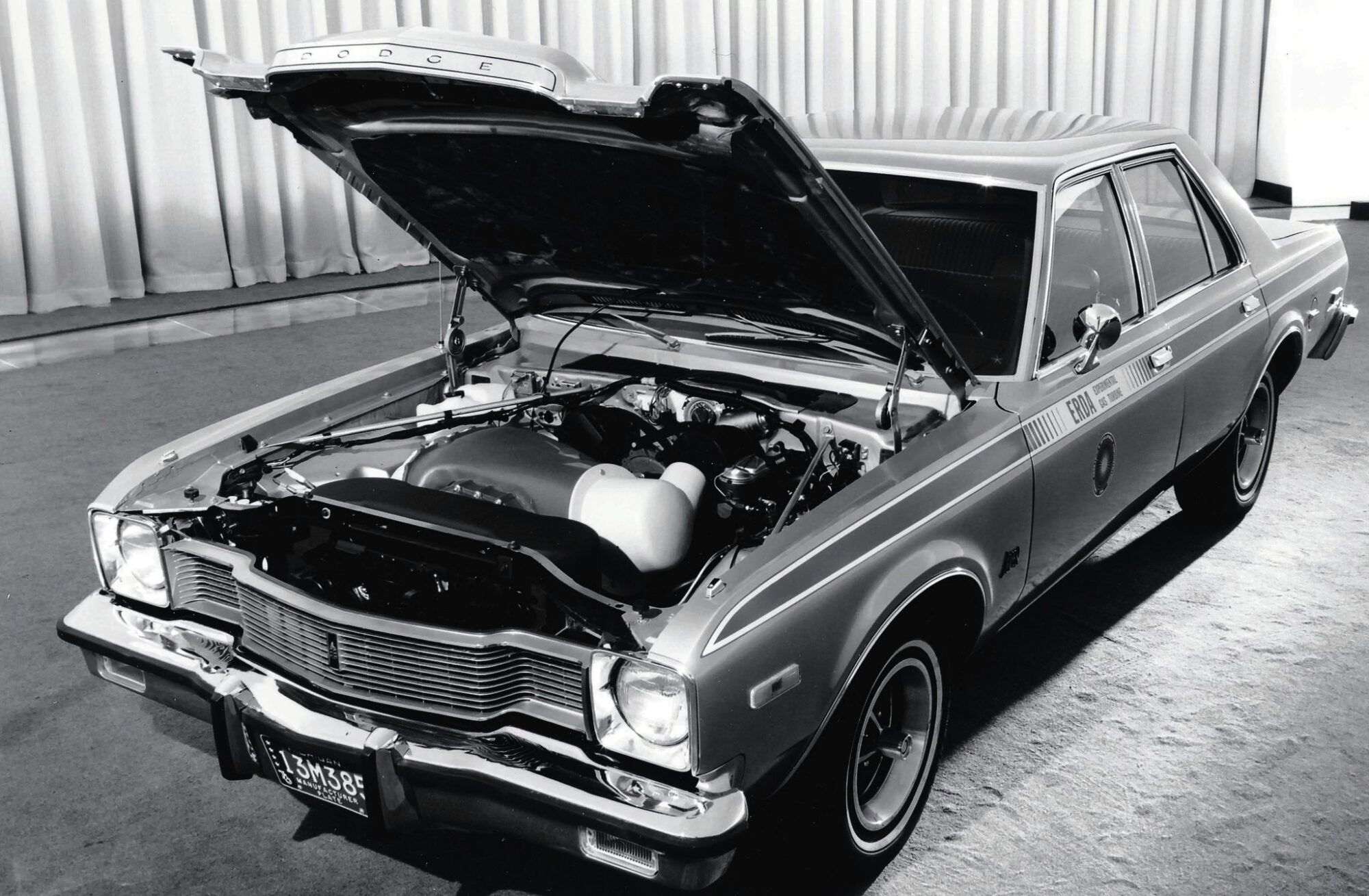

CONVERTED DODGE ASPEN

By the time the program got around to installing a new 7th generation turbine into a 1977 production Dodge Aspen 4-door sedan, the program had clearly lost its luster as being something exciting! At this point the focus wasn’t aimed at car enthusiasts but more for uses such as for taxicab fleets or government vehicles.

ON DISPLAY

This is a surviving 1963 “A-831” turbine engine, it had a horsepower rating of 130 and delivers an impressive 425 lb.-ft. of torque instantly. It was the fourth-generation of the engine and the challenges of controlling the nitrogen oxides in emission testing was the main problem of the program moving forward.

Looking back on history, the saga of the Chrysler turbine program is an interesting study of ingenuity in action, a passion for the pursuit of doing something different, plus a fantastic lesson in how to gather loads of publicity. The only question that remains, and only because of that fact that the mass production of the car did not happen, did all the energy and effort and money spent on it help sell Chrysler products in general? It seems in a sense that the entire “hook” of promoting turbine power for automotive use was that it could be the wave of the future, something that would be better than the piston-powered automobiles that everybody was buying and driving. Some ideas don’t pan out, but engineers try hard to find new technologies in order to improve current products. In this case, the turbine powerplant had to not only be as good as the piston-powered cars, it had to be better, and it wasn’t. A fascinating time in American automotive history nonetheless

REMEMBERING GEORGE HUEBNER

Known as the “father of the automotive gas turbine engine,” George J. Huebner joined Chrysler Corporation in 1931 as a laboratory engineer in the mechanical laboratories of the Engineering Division. He worked directly with Carl Breer, one of three engineers who had designed the very first Chrysler vehicle in the early 1920s. After WWII, Chrysler was awarded a contract from the U.S. Navy to design a 1,000 horsepower turboprop aircraft engine, and George was named Chief Engineer. Under his direction, Huebner organized a complete missile facility (including research, engineering and production) and enlarged the activities of Chrysler into the fields of physics, metallurgy and chemistry. All this hands-on experience led to his interest in adapting turbine power to automobiles. “In our windmill,” he once said, “we make our own wind. The burner is our sun and the compressor is our atmosphere.” He retired from Chrysler in 1975 when he was 65 years old and went on to work for Volvo of Sweden for eight years. He held more than 40 patents in the gas turbine automotive fields. In 1996 He died at the age of 86.

Author: James Maxwell

0 Comments