Chopped Volvo Became Sport Fury

There are those who still possess their favorite car, one they’ve owned for decades, and can vividly recall how they bought it 20-30 years ago. They remember the purchase price and the trip home, the feeling and excitement. Hasse Eklund is one such person, but his 1964 Sport Fury journey doesn’t begin traditionally. Instead, it starts with a somewhat unusual car trade.

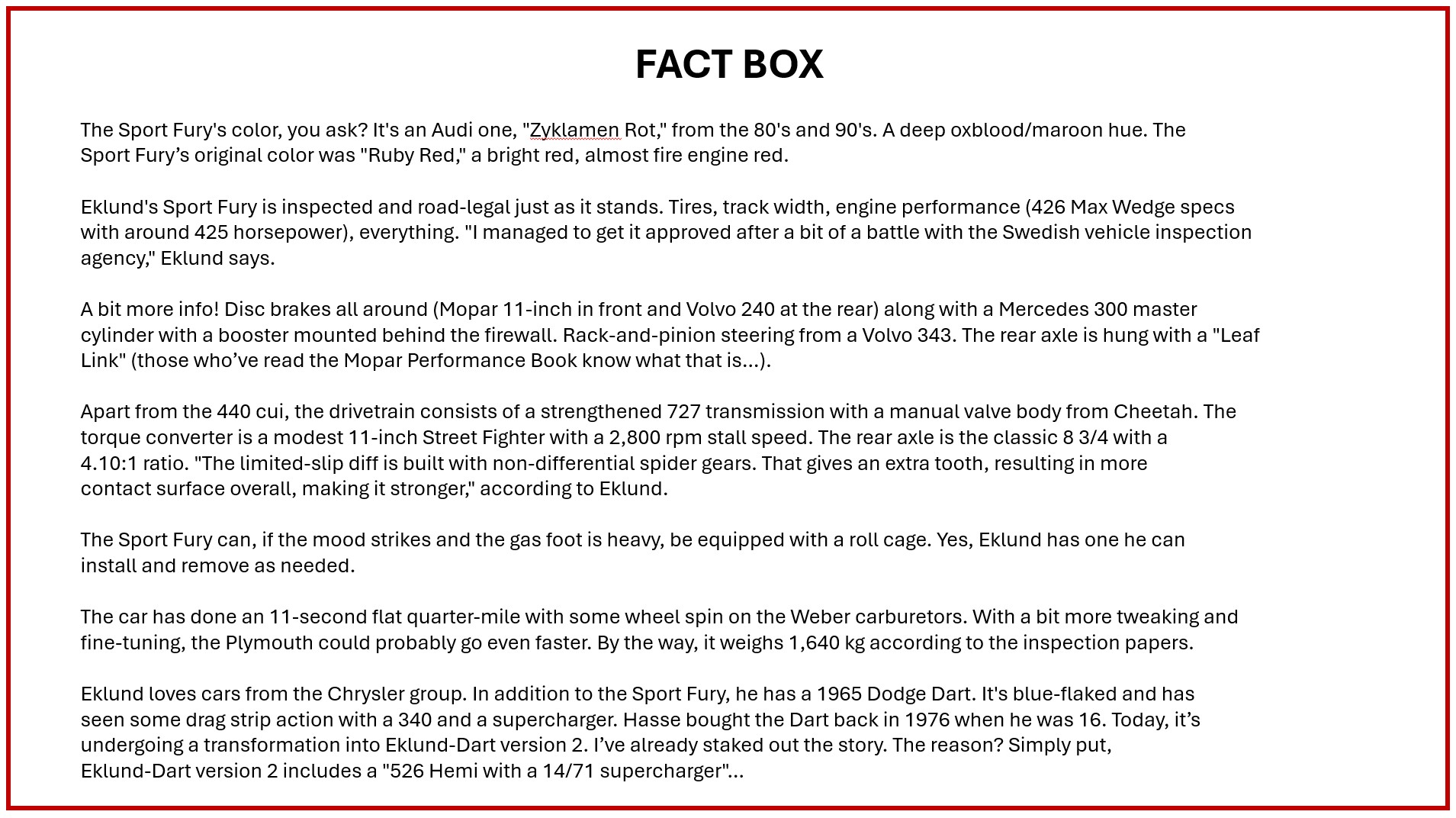

“I bought the car in 1988. Well, ‘bought’ might not be the right word. I traded it with my friend Raimo. I had a chopped-top pink Volvo Amazon with a B20 engine and a supercharger. Raimo had a 1964 Plymouth Sport Fury. It was a fair swap,” says Eklund.

The difference between the Amazon and the Sport Fury, besides being two different cars, was that the latter came in boxes, without a transmission or engine. Eklund, who was initially unsure if all the parts were included, eventually realized that most of it was there. Only some chrome trim was missing, as well as parts of the interior, like the front seats.

The car sat for a few years. Eklund, who was also racing his T23 Altered on the country’s drag strips, had other things to focus on. And he needed to gather a few parts.

“The first plan was to just throw it together and have a street car. But then, I like things that are shiny and nice. Rust has always been my lifelong enemy,” Eklund says.

So, he decided to repair the few rusted parts of the body, mainly the rear fender edges. He didn’t need to widen the rear wheel arches, though, as Raimo had already taken care of that.

Then, Eklund got hold of a 440-cubic-inch V8 and a 727 transmission, and the powertrain build was underway.

“I had a coworker back then named Göran. He’s good at tuning rally cars. Together, we agreed that it would be cool to put four Weber carburetors on a big V8,” Eklund says.

The choice of carburetors was logical given Göran’s rally background: a quartet of Weber 55s. Hasse made custom intake manifolds for them. After a bit of porting on the heads, it was time to look over the rotating assembly of the engine.

“I came across a stroked crankshaft, which I invested in. This was back when you couldn’t just buy ready-made stroker kits, you know. Along with that, I made my own connecting rods. I seem to recall we used tool steel, SS 2260. They ended up like billet rods, with an H-profile. In hindsight, the rods were a bit too heavy, but they held up for many years,” Eklund recalls.

The Sport Fury was completed in 1995. The following year, it took first place in the Street Machine competing class at Europe’s biggest car show Power Meet in Västerås, the southern Swedish city where Eklund lives.

After that, Eklund enjoyed the car for several years, while constantly but modestly improving it. Then one day, during a Power Meet day, Eklund started teasing his beloved partner into doing a proper burnout. “I can show you how it’s done,” he said.

“My partner participates in the women’s rally in town every year. At first, she was completely against the idea. ‘I’m not doing something like that,’ she said firmly. But as the day wore on… By the time we got to the little town Hallstahammar, it was first gear and full throttle. The tachometer probably spun around twice…” Eklund says with a laugh.

And just like that, the crank bearing failure happened, but Eklund could only grin and bear it. After all, these cars are meant to be used.

New plans were made for Eklund and his Sport Fury. At the time of the failure, tunnel ram intakes were the hot trend, so he got one. The stroked crank had survived fine, and just resurfacing the bearing journals was enough. Along with that, Eklund had two pre-assembled Megasquirt ECU kits lying around. Naturally, fuel injection had to be tested.

“I read somewhere that you could get at least 60 extra horsepower from a tunnel ram. However, I had to replace the mechanical camshaft. It didn’t work well with the stiff valve springs and modern oils, which are increasingly zinc-free due to all the catalytic converters. So, I installed a roller cam instead. On top of that, I used ceramic roller rockers from Schubeck. They’re made of titanium with ceramic rollers. Supposedly better than needle-bearing rockers, and they’ve held up,” Eklund says.

With custom-made throttle bodies and an injection system you didn’t find in just any street machine back then, there was a lot of trial and error to get it working. But in the end, it worked well, so well that Eklund still uses the same setup today.

The long-awaited massive fuel consumption reduction, however, did not materialize.

“With the Webers, I was averaging around 30 liters per 100 km. 25 liters if I drove a bit faster. Today, it’s around 22 liters per 100 km,” Eklund says.

The conversation shifts to the rest of the drivetrain before we wrap up the interview with some background on the Sport Fury. It’s actually a Swedish-sold car, first driven on the roads of Sweden on April 30, 1964.

“The car has been in Västerås for many years. After that, I’m not sure, but I’ve heard that it started its life as some kind of executive car in Sundsvall,” Eklund recalls.

Not bad. The Sport Fury’s journey begins in style, and the miles that followed are nothing to be ashamed of. When it now turns 60 years old, the Sport Fury is set to be more vital than ever.

0 Comments